Buddhist deities

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2021) |

Buddhism includes a wide array of divine beings that are venerated in various ritual and popular contexts. Initially they included mainly Indian figures such as devas, asuras and yakshas, but later came to include other Asian spirits and local gods (like the Burmese nats and the Japanese kami). They range from enlightened Buddhas to regional spirits adopted by Buddhists or practiced on the margins of the religion.

Buddhists later also came to incorporate aspects from the countries to which it spread. As such, it includes many aspects taken from other mythologies of those cultures.

Buddhas

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Buddhism |

|---|

|

A Buddha is a being who is fully awakened and has fully comprehended the Four Noble Truths. In the Theravada tradition, while there is a list of acknowledged past Buddhas, the historical Buddha Sakyamuni is the only Buddha of our current era and is generally not seen as accessible or as existing in some higher plane of existence. The Pali literature of the Theravāda tradition includes tales of twenty-nine Buddhas, which are Sakyamuni and the twenty-eight Buddhas who preceded him.

Mahayana Buddhists venerate numerous Buddhas, more so than the Theravada tradition, including Maitreya and Amitābha, who are seen as beings of great wisdom and power who preside over pure lands that one can travel to after death. Mahayana and Vajrayana traditions also recognize five primary Buddhas:

- Vairocana ("the Illuminator"), a key figure in the Avatamsaka Sutra and the Vairocanābhisaṃbodhi Sūtra. He is the central Buddha in Huayan Buddhism, Chinese Esoteric Buddhism, and Shingon. His pure land is known as the Padmagarbhalokadhātu (the lotus treasury world) and also as "Densely Arrayed Akaniṣṭha" (Ghanavyūhakaniṣṭha).

- Akshobhya ("the Imperturbable"), his buddha-field is Abhirati (lit. "The Joyous").

- Amitābha (Amida Buddha, "Infinite Light"), the principal Buddha of Pure Land Buddhism. His buddha field is called Sukhāvatī ("Blissful").

- Amoghasiddhi ("Infallible Success")

- Ratnasambhava ("Jewel Born")

Each is associated with a different consort, direction, aggregate (or aspect of the personality), emotion, element, color, symbol, and mount.[1] In later, especially tantric sources, each male Buddha is associated with a specific female Buddha (though their names and attributes vary across the various Buddhist sources). Here is one common list of the five female Buddhas (also called prajñās, or vidyas):[2][3]

- Ākāśadhātvīśvarī ("The Sovereign Lady of the Sphere of Infinite Space"), the prajñā of Vairocana

- Locanā, the prajñā of Akṣobhya

- Māmakī ("Mine-maker"), the prajñā of Ratnasambhava

- Paṇḍāravāsinī ("White Robed One"), the prajñā of Amitabha

- Tārā ('Star"), sometimes associated with Amoghasiddhi, sometimes Amitabha

In Tibetan Buddhism, several female Buddhas are also recognized, such as Tara, the most popular female Buddha in Tibetan Buddhism, who comes in many forms and colors. Other female Buddha figures include Vajrayogini, Nairatmya, and Kurukullā.

Other Buddhas besides these five include Bhaisajyaguru (the Buddha of medicine) and Nageshvara Raja (the king of the Nāgas).

There is also the idea of the Adi-Buddha, the "first Buddha" to attain Buddhahood. Variously named as Vajradhara, Samantabhadra, Shiva, and Mahavairocana, the first Buddha is also associated with the concept of Dharmakaya and the Ground of all phenomena.

Some historical figures are also seen as Buddhas, such as the Buddhist philosopher Nagarjuna (sometimes called the second Buddha) and the figure of Padmasambhava.

Bodhisattvas

[edit]

In Theravada Buddhism, bodhisatta is a term used mainly for Sakyamuni Buddha before his awakening. It is also commonly believed that the future Buddha, Maitreya (Pali: Metteya) currently resides in Tushita Heaven, and this figure is one of the few bodhisattvas who have a prominent place in Theravada.[4][5]

In Mahayana Buddhism, a bodhisattva is any being that has aroused bodhicitta (mind of awakening) and is thus working towards full Buddhahood. Bodhisattvas who are seen as powerful and highly advanced are highly venerated in this tradition.

In India, a list known as the "Eight Close Sons" (Skt. aṣṭa utaputra) became the main set of bodhisattvas of Shakyamuni Buddha's entourage, they are:[6][7]

- Mañjuśrī ("Gentle Glory") Kumarabhuta ("Young Prince"), the main bodhisattva of wisdom

- Avalokiteśvara ("Lord who gazes down at the world"), the savior bodhisattva of great compassion

- Vajrapāṇi ("Vajra in hand"), the bodhisattva of protection, the protector of the Buddha (in East Asian sources, this slot is taken by Mahāsthāmaprāpta, though Vajrapāṇi is also found in these traditions)

- Maitreya ("Friendly One"), will become the Buddha of our world in the future

- Kṣitigarbha ("Earth Source"), known as the savior of beings from hell

- Ākāśagarbha ("Space Source") also known as Gaganagañja, associated with the space element (ākāśa).

- Sarvanivāraṇaviṣkambhin ("He who blocks the hindrances")

- Samantabhadra ("Universal Worthy", or "All Good"), associated with vows

In Tibetan Buddhism, a Vajrayana Buddhist tradition, the major bodhisattvas are these "eight great bodhisattvas".[8]

The bodhisattva Prajñāpāramitā-devi is a female personification of the perfection of wisdom and the Prajñāpāramitā sutras. She became an important figure, widely depicted in Indian Buddhist art. She is the main female bodhisattva in Indian sources. Other Mahayana sutras also depict female bodhisattvas, such as The Lion's Roar of Śrīmālādevī.[9]

Other male bodhisattvas appearing in Indian sources include Candraprabha, Suryaprabha, Bhaiṣajyasamudgata, Bhaiṣajyarāja, Akṣayamati, and Vajrasattva. There are also other female bodhisattvas like Tara, Ushnishavijaya, Vasudhara and Cundi.

In the East Asian Buddhist traditions, which are mainly Mahayana, major bodhisattvas include many of the above: Guānyīn (Japanese: Kannon), Maitreya (Chinese: Mílè, Jp: Miroku), Samantabhadra (Ch: Pǔxián, Jp: Fugen), Manjushri (Wénshū), Ksitigarbha (Ch: Jìzàng Jp: Jizō), and Akasagarbha. The most popular bodhisattva in the East Asian pantheon is surely Guānyīn (the East Asian form of the Indian Avalokitesvara) who is depicted as female in East Asia, rather than as the Indian male Avalokitesvara. Guanyin is also believed by Buddhists to take on numerous manifestations, among which are several other bodhisattvas such as Cundi and Cintamanicakra.

In addition, Buddhist traditions in different countries have also absorbed native deities into their localized Buddhist pantheon, sometimes as Bodhisattvas. Some examples are Guan Yu in Chinese Buddhism, who is venerated as Sangharama Bodhisattva (Chinese: 伽藍菩薩; Pinyin: Qiélán Púsà) as well as a deity, and Hachiman in Japanese Buddhism, who is venerated as the Bodhisattva Hachiman (Japanese: 八幡大菩薩; Rōmaji: Hachiman Daibosatsu).

Certain historical figures have been considered to be bodhisattvas, like Nagarjuna. Followers of Tibetan Buddhism consider reborn tulkus such as the Dalai Lamas and the Karmapas to be emanations of bodhisattvas. East Asian Buddhist traditions may venerate certain historical figures as bodhisattvas, such as Kukai in the Shingon school.

Protector deities

[edit]In Buddhism, there is a class of deities whose main role is to act as guardians, protectors or general removers of evil. Some of these are unique to Buddhism and others are Indian deities that Buddhism shares with Hinduism.

In Mahayana Buddhism there are numerous "dharma protectors" (S. dharmapāla, T. chos skyong; C. fahu 法護), powerful beings who are defenders of Buddhism and protectors of Buddhists against evil or harm.[10] There are two main types of protectors, mundane worldly protectors (who may be devas or spirits) and supramundane awakened protectors, bodhisattvas or buddhas who appear in a specific form to defend the Dharma.[10] The former includes numerous devas such Brahmā and Indra, as well as local spirits and gods that have been adopted by Buddhism. The latter type include popular wrathful deities like: Yamantaka, Ekajaṭī, Mahākāla, Palden Lhamo, and Hayagrīva.

Guardians of the world

[edit]

The four "guardians of the world" (lokapāla), also known as the Four Heavenly Kings (Cāturmahārāja), are four deities (devas) who protect the four directions of the Sahā world (our world). Each guardian rules over a specific direction and also a class of non-human beings. These guardian deities are found in the earliest Buddhist sources and are shared by Mahayana and Theravada. The four guardians are:[11]

- Dhṛtarāṣṭra (Sanskrit; Pali: Dhataraṭṭha) - Guardian of the East. Leader of the gandharvas and piśācas.

- Virūḍhaka (P: Virūḷhaka) - Guardian of the South. Leader of the kumbhāṇḍas and pretas.

- Virūpākṣa (P: Virūpakkha) - Guardian of the West. Leader of the nāgas and pūtanas.

- Vaiśravaṇa (P: Vessavaṇa) - Guardian of the North. Leader of the yakṣas and rākṣasas.

Wisdom King

[edit]

The Wisdom Kings (Sanskrit: Vidyārāja) are beings that are venerated in East Asian Buddhism and in Vajrayana Buddhism. They are often depicted with an aggressive or fierce appearance which symbolizes their power to get rid of negative forces. They are thus often seen as an expression of the Buddha's compassion.

In East Asian Buddhism, The Five Wisdom Kings are often seen as emanations of the Buddhas. These five are:

Other important Wisdom Kings include

Five Protector Goddesses

[edit]The Pañcarakṣā ("Five Protectors") are five protector goddesses which are important in Mahayana Buddhism, the term also refers to their dhāraṇīs.[12][13][14][15]

These five protective dhāraṇī-goddesses are:[12]

- Mahāpratisarā (known for protection against defilements, disease, and evils),

- Mahāsahasrapramardinī (for protection against evil spirits),

- Mahāmāyūrī or vidyārājñī (for protection against snake-poison),

- Mahāśītavatī (for protection against 'cruel' planets, cruel animals, and poisonous insects), and

- Mahārakṣā mantrānusāriṇī (for protection against diseases).

Mundane Dharmapalas

[edit]

In Chinese Buddhism, there is a list of Twenty-Four Protective Deities (Chinese: 二十四諸天; pinyin: Èrshísì Zhūtiān). These are mostly mundane dharmapalas:[16]

- Maheśvara (Shiva)

- Brahma

- Śakra (Indra)

- Lakshmi

- Sarasvati

- Vaiśravaṇa

- Virūḍhaka

- Dhṛtarāṣṭra

- Virūpākṣa

- Surya

- Chandra

- Guhyapāda

- Pañcika

- Skanda

- Pṛthvī

- Spirit of the Bodhi Tree

- Hārītī

- Mārīcī

- Sāgara

- Yama

- Kinnara King

- Emperor Zi Wei

- Emperor Dongyue

- Thunder God

Devas

[edit]

The term deva (Sanskrit; Pāli: deva; Tibetan: lha; Chinese: tian 天; Japanese: ten; Korean: cheon) literally means "radiant one" or "shining one" and is commonly translated as "divinity," "heavenly being," or "god." Devas are one of the five (or six, in some traditions) realms of rebirth (gati) within the cycle of existence (saṃsāra).[17] The word deva originates from the Sanskrit root √div, meaning "to shine," and shares an etymological connection with the English word "divinity." Rebirth as a deva is considered a favorable outcome resulting from virtuous deeds (karman) performed in previous lifetimes. While the heavenly realms of devas are regarded as auspicious, they are impermanent and remain part of the cyclic existence of saṃsāra, rather than being eternal heavens.[17] Devas are not all necessarily wise or on the Buddhist path and hence not objects of refuge. They have very long lives which have much less suffering than humans, but are not immortal or immune from suffering. Some devas have no physical form and exist in the formless realms. None of them are creator gods, and they are neither omniscient nor omnipotent.[17]

Buddhist cosmology identifies 27 (alternatively 26 or 28) categories of devas, classified based on their dwelling places (devaloka) within the three realms of existence (trailokya): the sensuous realm (kāmadhātu), the material or form realm (rūpadhātu), and the formless or immaterial realm (ārūpyadhātu).[17] Devas are apparitional beings, appearing fully developed at birth. In the sensuous realm, they retain physical bodies and consume food, while those in higher realms subsist on subtler forms of nourishment, such as sensory contact or mental contemplation.[17] Their existence, while pleasurable, remains impermanent, as they are bound by saṃsāra. Upon rebirth, devas are often aware of their past lives and the virtuous deeds that led to their celestial existence.[17]

Some of the most commonly discussed types of devas in Buddhist scriptures include: the Brahma devas, Trāyastriṃśa devas, gandharvas (celestial musicians), and the Tuṣita devas.[17]

Various Indian devas were part of Indian Buddhism from an early period. Examples include Śakra (known as "lord of the devas", the Buddhist Indra) who rules over the devas of the "Heaven of the Thirty Three" (Trayatrimsa), the four Lokapalas ("guardians of the world"), and goddesses like Lakshmi and Hariti.

With the spread of Buddhism out of India, different cultures also integrated or syncretized local deities into their pantheon of devas. For example, Chinese Buddhism venerates the Twenty-Four Protective Devas, which include both originally Indian deities, such as Mahesvara (Shiva), Sakra (Indra), Brahma, Sarasvati, Laksmi, Marici and Hariti, as well as a few deities integrated from Taoism, such as the Emperor Zi Wei and Leigong. Guan Yu, who is regarded as a god of war in Taoism, is also regarded as both a bodhisattva and a deva.

In Japanese Buddhism, Shinto gods were also syncretized into the pantheon under the honji suijaku theory by being conflated with the Indian deities imported from Buddhism, such as Ugajin and Ōkuninushi.

Yidam

[edit]

The yidam, or ishta-devata, is a personal meditation deity. The Sanskrit word iṣṭadevatā or iṣṭadevaḥ is defined by V. S. Apte as "a favorite god, one's tutelary deity."[18] Though this term is used in many popular books on Buddhist Tantra, the term işţadevatā has not been attested in any Buddhist tantric text in Sanskrit. The unrelated Tibetan version of the term, possibly of entirely native origin, is yi-dam[19] is said to be a contraction of Tib. yid-kyi-dam-tshig,[20] meaning "samaya of mind"- in other words, the state of being indestructibly bonded with the inherently pure and liberated nature of mind.

The ishta-devata of Hinduism is an aspect of God for personal worship.[21] In Buddhism, a yidam is a manifestation of enlightenment and may take the form of Sambhogakāya Buddhas, tantric deities such as Dakinis, bodhisattvas, Dharma protectors (Dharmapalas) or other historical figures such as past gurus or religious leaders.[20]

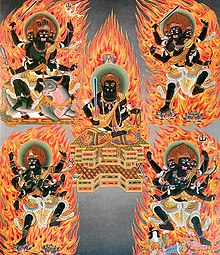

Wrathful deities

[edit]In the Buddhist Tantras, Buddhas and Bodhisattvas often manifest in unusual and fierce forms, which are used in tantra as yidams or meditation deities.[22] While some of these deities have a hideous and fierce appearance, they are not personifications of evil or demonic forces. The ferocious appearance of these deities is used to instill fear in evil spirits which threaten the Dharma.[23]

Other beings

[edit]

Throughout the history of Buddhism, Buddhists have also venerated and relied on numerous other supranormal beings or spirits.

One important class of beings are the yakṣas, nature-spirits, usually benevolent, who are caretakers of the natural treasures hidden in the earth and tree roots.[24] Having been worshiped in India since before the Vedic period, Buddhists in India venerated these deities as local protector spirits. One important Indian yakṣa was Kubera, the spirit of wealth.[25]

Another important class of beings are the nāgas, a serpentine race of beings, often associated with protecting bodies of water. These beings are also associated with the Mahayana sutras and their protection.

In Burma there exists the popular worship of nature spirits called nats which are worshiped alongside of Buddhism.[26]

In Japan, Buddhists have traditionally venerated the local kami deities.

See also

[edit]- Buddhist cosmology

- Chinese gods and immortals

- Hindu deities

- Japanese Buddhist pantheon

- Karma in Buddhism

- Religion in Asia

References

[edit]- ^ Williams, P.; Tribe, A.; Wynne, A. (2002). Buddhist Thought: A Complete Introduction to the Indian Tradition. India: Taylor & Francis. p. 211.

- ^ Vessantara (2014), Female Deities in Buddhism. Windhorse Publications.

- ^ "Buddhist Mantras - Mantras of Buddhas, Bodhisattvas and other archetypal figures, plus miscellaneous mantras and chants". www.visiblemantra.org. Retrieved 2023-12-07.

- ^ Leighton, Taigen Dan (2012). Faces of Compassion: Classic Bodhisattva Archetypes and Their Modern Expression — An Introduction to Mahayana Buddhism. Simon and Schuster. p. 246.

- ^ Jory, Patrick (2016). Thailand's Theory of Monarchy: The Vessantara Jataka and the Idea of the Perfect Man. SUNY Press. p. 72.

- ^ Dalai Lama XIV Bstan-ʼdzin-rgya-mtsho, Dalai Lama XIV, Dalai Lama, Santideva (1994). A Flash of Lightning in the Dark of Night: A Guide to the Bodhisattva's Way of Life, pp. 128-129, note 23. Shambhala.

- ^ Wang, Michelle C. (2017) Maṇḍalas in the Making: The Visual Culture of Esoteric Buddhism at Dunhuang, p. 158. BRILL.

- ^ Mipham, Jamgon (2008). Garland of Jewels: The Eight Great Bodhisattvas. United States: KTD Publications.

- ^ "The Inquiry of Lokadhara, Introduction". 84000 Translating The Words of The Buddha. Archived from the original on 2022-01-01. Retrieved 2022-01-01.

- ^ a b Buswell, Robert E; Lopez, Donald S. The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism, pp. 249-250. Princeton University Press, Nov 24, 2013.

- ^ Buswell, Robert E; Lopez, Donald S. The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism, pp. 230-233. Princeton University Press, Nov 24, 2013.

- ^ a b "Dictionary | Buddhistdoor". www2.buddhistdoor.net. Retrieved 2024-01-10.

- ^ K. R. van Kooij (1978). Religion in Nepal. BRILL Academic. pp. 25–27. ISBN 90-04-05827-3.

- ^ Adalbert J. Gail; Gerd J. R. Mevissen; Richard Salomon (2006). Script and Image: Papers on Art and Epigraphy. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 57–58. ISBN 978-81-208-2944-2.

- ^ Thomas E. Donaldson (2001). Iconography of the Buddhist Sculpture of Orissa: Text. Abhinav Publications. pp. 295–296. ISBN 978-81-7017-406-6.

- ^ Lewis Hodous; William Edward Soothill (2004). A dictionary of Chinese Buddhist terms: with Sanskrit and English equivalents and a Sanskrit-Pali index. London: RoutledgeCurzon. ISBN 0-203-64186-8. OCLC 275253538.

- ^ a b c d e f g Buswell, Robert E; Lopez, Donald S. The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism, pp. 230-233. Princeton University Press, Nov 24, 2013.

- ^ Apte, Vaman Shivaram (2014). The Practical Sanskrit Dictionary. Motilal Banarsidass. p. [page needed]. ISBN 978-8120805675.

- ^ Blofeld, John (1992). The Tantric Mysticism of Tibet: A Practical Guide to the Theory, Purpose, and Techniques of Tantric Meditation. Penguin.

The function of the Yidam is one of the profound mysteries of the Vajrayana... Especially during the first years of practice the Yidam is of immense importance. Yidam is the Tibetan rendering of the Sanskrit word Istadeva-the indwelling deity; but, where the Hindus take the Istadeva for an actual deity who has been invited to dwell in the devotee's heart, the Yidams of Tantric Buddhism are in fact the emanations of the adepts own mind.

- ^ a b Harding, Sarah (Spring 2005). "The Dharma Dictionary". Buddhadharma: The Practitioner's Quarterly.

- ^ Pandit, B. (2005). Explore Hinduism. United Kingdom: Heart of Albion. p. 173.

- ^ Farrer-Halls, G. (2002). The Feminine Face of Buddhism. United States: Quest Books. p. 42.

- ^ Forrester, S. T. (2006). Dancing in the Fire of Transformation. Flute Player Publications. pp. 357–358.

- ^ "Yaksha". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2007-07-15.

- ^ Encyclopedia of World Art. Vol. 13. United Kingdom: McGraw-Hill. 1959. p. 831.

- ^ Powell, A. (1995). Living Buddhism. United States: University of California Press. p. 59.

Further reading

[edit]- Campbell, Joseph (2003). Myths of Light: Eastern Metaphors of the Eternal. Novato, California: New World Library. ISBN 1-57731-403-4.

- Garson, Nathaniel DeWitt (May 2004). Penetrating the Secret Essence Tantra: Context and Philosophy in the Mahayoga System of rNying-ma Tantra (PhD dissertation). Retrieved 2024-01-11.